Founded in 1966, the Duke Lemur Center (DLC) houses the world’s largest and most diverse population of lemurs outside of Madagascar and contributes to conservation efforts through noninvasive research, research that does not involve harming or, in most cases, touching the lemurs.

Johann, a Coquerel's sifaka, spends time in the trees on Tuesday, March 28, 2023. The Duke Lemur Center (DLC) in Durham, N.C., leads the world in the study and conservation of lemurs, the most endangered mammals on Earth. Lemurs contribute to the biodiversity of Madagascar by providing essential ecosystem services such as seed dispersal and pollination. These services are necessary for reforestation efforts. Today, 98% of lemurs are endangered, and 31% of species are critically endangered. Lemurs face several threats, including habitat loss and fragmentation, frequent and extreme weather events, changing climate, and poaching. Much of the DLC’s research consists of observing the behaviors of free-ranging lemurs like Johann and his partner, Rodelinda, and their baby, Egeria.

Meg Dye, the DLC’s Curator of Behavioral Management and Welfare, leads a training session with Sputnik, a three-year-old Black-and-white ruffed lemur. Sputnik will participate in a research study that compares the force exerted during vertical leaps between two diurnal lemurs, lemurs that are active during the day, one of which is a natural vertical leaper and the other which is not. Sputnik is not a natural vertical leaper; therefore, he must learn the behavior before the trial. “He's a go-getter,” Dye said. “I can keep increasing the height, and he gives it his best to get up there as high as he can.”

DLC research technician Gabbi Hirschkorn and research team conduct cognition trials with Camilla, a two-year-old Coquerel's sifaka. The trials evaluate the lemur’s understanding of tasks, rewarding actions with grape skin “treats.” Studying lemur cognition gives insight into the development of mental abilities in lemurs, the earliest primate ancestors of humans. “We learn a lot about how they think, how they learn in the process and just how intelligent they are,” said Erin Ehmke, Ph.D., Director of Research at the DLC.

Herschel, a 10-year-old Black-and-White Ruffed Lemur, pulls on a string contraption, bringing the grape skin “treat” closer to him. Researchers use food rewards to encourage lemurs’ voluntary participation in research trials. In this cognition trial, Herschel understands that pulling on the orange string dish will result in a reward. “They enjoy that enrichment that they get from participating in the studies, and they're eager to participate, especially if there are snacks involved,” said Alexis Sharp, Research Manager at the DLC.

Nine-year-old Ring-tailed lemur LuLu jumps from one elevated bar to another during locomotion trials. “Lemurs are an arboreal species, meaning they hang out in the trees,” Sharp shared. They’re known to leap great distances from tree to tree in the wild. During the locomotion trials, a DLC research technician cues the lemur to jump across three elevated bars, varying in distance. “It's really important for those animals to be able to safely move among the trees and be able to calculate distance and understand the force that they need to leap and jump with and to avoid things like falls,” Sharp added. By recording the locomotion trials, researchers at the DLC analyze the physical adaptations that allow lemurs to leap from one surface to another.

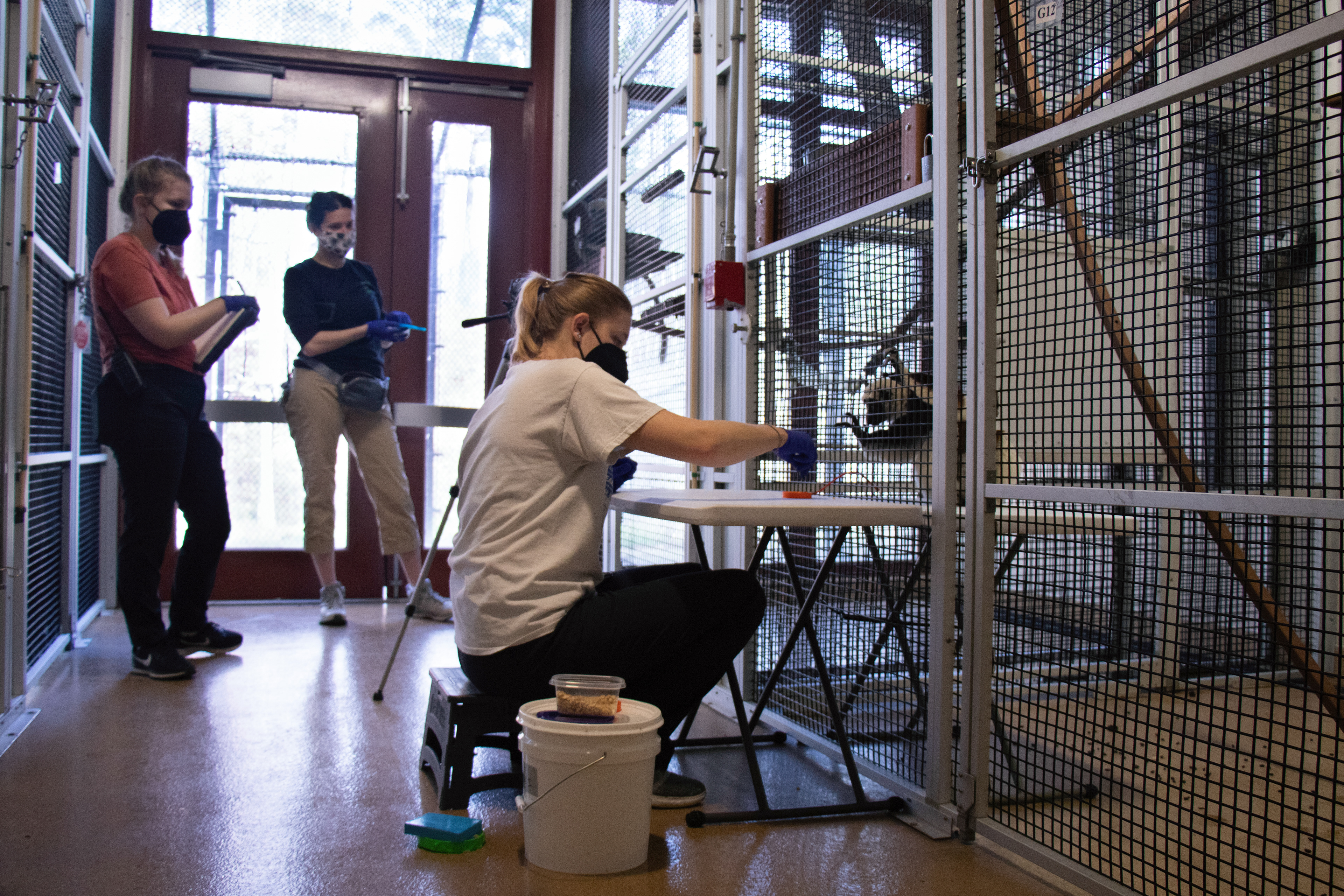

DLC researchers set up equipment and cameras ahead of locomotion trials with bush babies. Although researchers can set up equipment in LED light, red light must be used during research trials with nocturnal animals. Because bush babies cannot see red light, it does not influence behavior or hurt their eyes during trials. The locomotion trials examine the force exerted by a bush baby when it jumps vertically from the force plate to a horizontal branch.

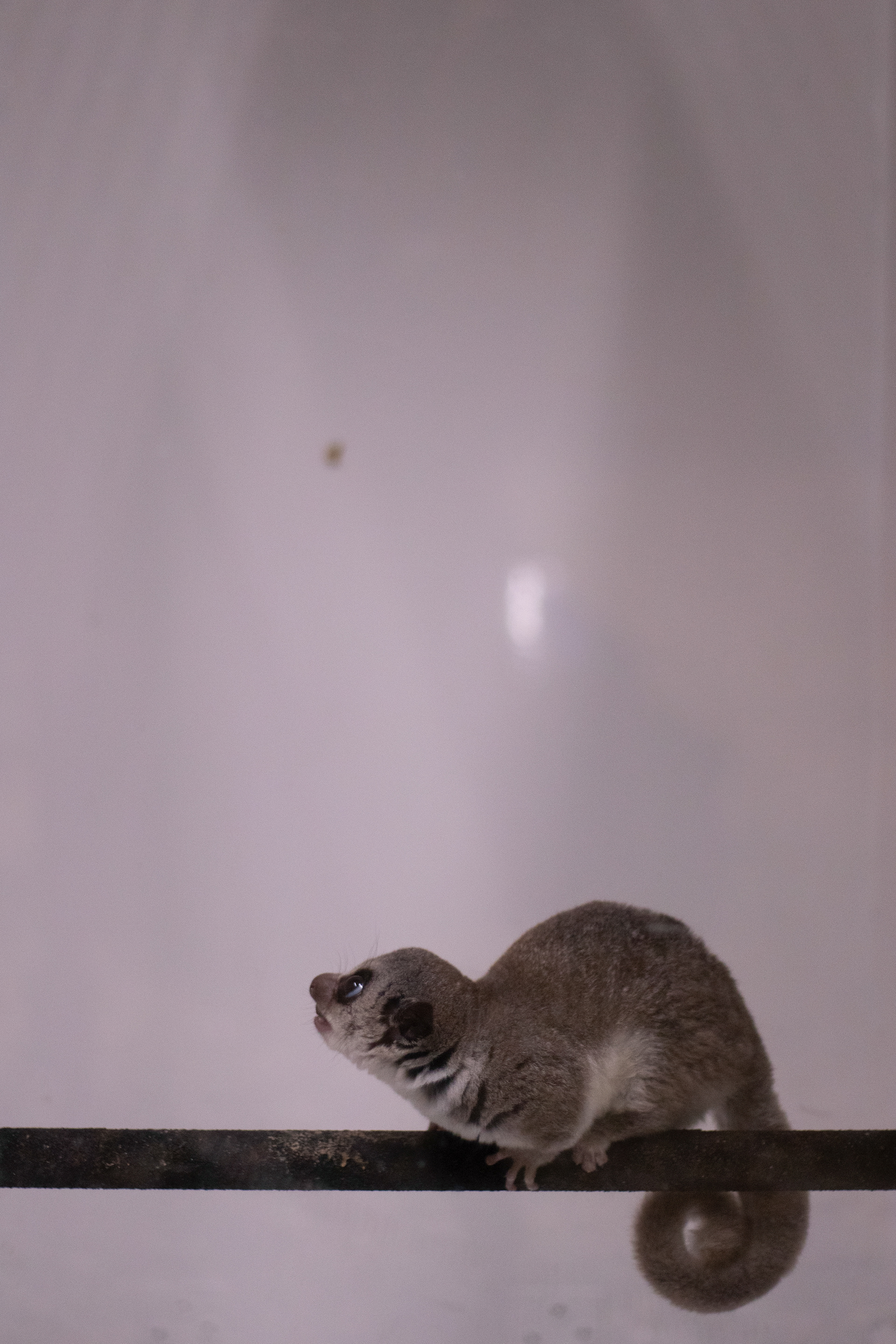

Elephant Bird, a four-year-old fat-tailed dwarf lemur, prepares to jump vertically from a tree branch on. DLC researchers continue locomotion trials with fat-tailed dwarf lemurs, recording the force of their vertical leaps.

DLC researchers record the grip strength of Quetzal’s left foot. The four-year-old fat-tailed dwarf lemur is one of the participants in a grip strength study that measures the grip strength of lemurs’ limbs, studying how it affects their ability to move in an arboreal environment. Lemurs have hands and feet specifically adapted to jump, climb, and hang from tree branches.

DLC researchers run locomotion trials with Albatross, a four-year-old fat-tailed dwarf lemur. In addition to collecting quantitative data, researchers record each trial on digital cameras. This allows trials to be reviewed at a later date.